Not Reading the Syllabus

Syllabi that reflect the mundane, bureaucratic requirements of the University are at risk of setting an equally banal classroom atmosphere.

Syllabi that reflect the mundane, bureaucratic requirements of the University are at risk of setting an equally banal classroom atmosphere.

— Adam Heidebrink-Bruno

A day or two before classes begin, I send my students an e-mail in which I advise, “Some people are under the mistaken impression that the first day of class is simply a time for the professor to read the syllabus to students before everyone goes home. This is not the case for [insert class name].”

Reading the syllabus to students is a mind numbing experience that wastes a valuable opportunity to build on the first day’s excitement by facilitating conversations between students.

Even reading to students the type of syllabus which Dr. Heidebrink-Bruno proposes in “Syllabus as Manifesto: A Critical Approach to Classroom Culture,” squanders the opportunity to establish rapport between students which result from the type of conversations which Dr. Jesse Strommel described in a recent discussion among faculty that took place on Facebook. Stommel doesn’t focus on the syllabus because he doesn’t “want to burden the first day with predeterminations.” He goes on to explain, “I talk about the class a little, but mostly we talk about ourselves and why we’re there (and about the subjects of the class). That is what will determine the shape of the course; not the ramblings I’ve done in a syllabus before even meeting the members of the group.”

At my college, we are required to give students a copy of the syllabus on the first day of class. But we are not required to present the syllabus as the first item of business. Nor are we even required to go over it. Therefore, like Strommel, on the first day of class I talk a little bit about some of the class expectations, but mostly I provide an environment where students are able to get to know each other.

On the second day of class, I ask students if they have any questions about the syllabus. Rarely are there any.

I am not so naïve as to think that my students actually read the syllabus between the first and second day of class. In fact, I assume that virtually none of them read it. This doesn’t bother me because, I would argue, students not reading the syllabus actually facilitates education because it allows me to put the focus on learning instead of on rules and regulations and assignments.

During the semester, I can cite aspects of the syllabus as they become relevant. For example, on the first day of class, there is really no valid pedagogical reason to explain the directions for the final reflection that students will not submit until the last week of the semester; three months after the first day of class. It is better to go over that portion of the syllabus during week 13 or 14.

Although some faculty members might be shocked that I don’t expect—or even care—if students immediately read the syllabus, I have the impression that many faculty members do not even read their own syllabi before distributing them to their students.

How many of us have inserted boilerplate language into our syllabi without reading it? I know that I have been guilty of not carefully reading boilerplate language. As a result, because some poorly written boilerplate language I inlcuded in the syllabus rightly took precedence over my classroom instructions, a student was once able to argue that she ought not to fail my class for academic dishonesty.

Recently, I became aware of a case where some boilerplate language included factually inaccurate information concerning a vital aspect of academic research. Bureaucratic procedures were going to cause a delay of several months to have the boilerplate language corrected. In the meantime, I suspect that many faculty members simply inserted the inaccurate language in their syllabi without reading it. If a student cites the boilerplate language to justify plagiarism or to ridicule the faculty member’s misunderstanding of academic integrity, those faculty members who did not read their own syllabi will be shocked to read what they distributed to their students on the first day of class.

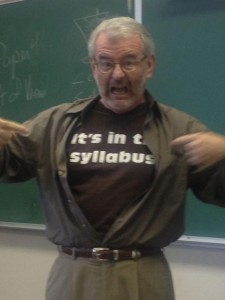

Earlier this week, Dr. Lisa Wade published “10 Things Every College Professor Hates.” Item #4 advises students to consult the syllabus before asking the professor a question. The photograph of Dr. David Lydic wearing a T-shirt that reads “It’s in the Syllabus” went viral last year and has reappeared as the new semester begins this fall. And I have already directed one of my students from this semester to consult the syllabus for an answer to a question she asked; a question answered in part of the syllabus I have already covered. There is a place for “mundane, bureaucratic requirements” in syllabi, but syllabi should be much more than that.

Syllabi should be living documents that are adapted and revised throughout the semester. They should not be the focal point of our courses; especially not on the first day of class.

- –Steven L. Berg, PhD

Photo Caption: Dr. David Lydic

I think reading the syllabus in class is not the Professor’s responsibility, students must read the syllabus just before class. It’s not a bad idea to read the syllabus to the students, it will make it easier for the teacher to communicate with students and reduces plenty of time for the coming sessions.