“Burn Those $%#@ Police Cars!”

I remember sitting in a dark auditorium at Michigan State University watching a documentary on the assassination of Harvey Milk. I knew the story of Milk’s murder before I entered the auditorium, but I was not prepared for my reaction to the violence in the film.

I remember sitting in a dark auditorium at Michigan State University watching a documentary on the assassination of Harvey Milk. I knew the story of Milk’s murder before I entered the auditorium, but I was not prepared for my reaction to the violence in the film.

Milk was the first openly gay man elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. On 27 November 1978, he and Mayor George Mascone were assassinated by Dan White. At his trial, White’s lawyer argued diminished capacity due, in part, to a junk food binge White had the night before the assignation. The “Twinkie defense” worked. White was convicted of voluntary manslaughter instead of first degree murder.

On 21 May 1979, after the verdict had been handed down, the White Night riots erupted in San Francisco. Watching the documentary, I saw 3,000 people come together to protest the jury verdict and, by extension, the treatment of LGBTQI+ people. It was exhilarating. But then came the violence.

I watched the riots begin. Then I saw the police car on fire. From somewhere deep in my subconscious, I silently screamed “Burn those fucking police cars!”

I was shocked at my reaction.

Even as a young man, I did not support violence. I had read Charles Weingartner and Neil Postman’s The Soft Revolution shortly after it was published in 1971 and took to heart their concept of non-violent confrontation. Violence, I believed, was inconsistent with effective political strategy.

Yet, there I was in a dark auditorium screaming to myself “Burn those fucking police cars!”

At that moment, I realized that I had a capacity for violence which, until then, had been hidden from me. I realized that, were I in San Francisco on 21 May 1979, I could have easily moved from peaceful protester to someone who would not hesitate to “Burn those fucking police cars!”

More than 40 years later, I have a better understanding of both my reaction and what can lead people to violent protest. Yet, as I tell my students, understanding is not the same as approving. However, the process of understanding can lead to empathy, self-reflection, and change.

Generally, violence is not the first line of defense. Violence is an action of last resort once other means of protest and social systems fail. As a young gay man, I had already experienced the systemic discrimination that was designed to hold me down. I had already learned that far too many people believed—and continue to believe–that my body is a legitimate receptacle for their violence. It is not surprising that I would respond to the continued threat of violence with violence. It makes sense that I would want to see police cars burn.

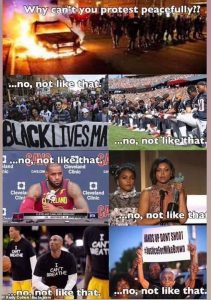

Over the past few days, I have read social media posts arguing that violence only begets violence. Therefore, protesters should not be violent. However, this analysis conveniently ignores that the cycle of violence did not begin with the protesters. Self-reflection requires that we ask ourselves, “How have I contributed to the cycle of violence that has erupted the past few days?”

Last night, the Pride At Work offices located in the AFL-CIO building two blocks from the White House were damaged. Pride At Work Executive Director Jerame Davis commented “We will fix the broken glass and sweep away the ashes so we can continue to fight for racial, social, and economic justice.”

Because I do not approve of the violence, I, too, will continue to fight for racial, social, and economic justice. The success of such work will ultimately create a society where “Burn those fucking police cars!” will never again be considered a viable option.

–Steven L. Berg, PhD

Postscript: Not all violence can be attributed to a lashing out of systemic oppression. Evidence mounts that a variety of extremist organizations have hijacked the peaceful demonstrations. The violence of such extremism is not the subject of my reflection.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

LEAVE A COMMENT